by Dan Neil

by Dan NeilWall Street Journal

January 28, 2012

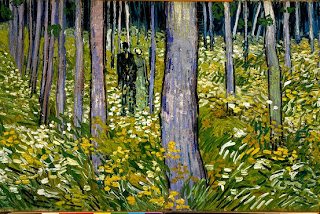

Vincent Van Gogh was a handful: almost certainly a victim of epilepsy, perhaps an alcoholic, maybe mad from the leaded paint he worked with, but in any case a raving, God-haunted lunatic most of the time and nobody's favorite neighbor.

Fortunately for him, and us, Van Gogh was able to self-medicate.

"Focus on a small detail of nature allowed him to keep a calm frame of mind," writes Anabelle Kienle, co-curator of the Philadelphia Museum of Art's "Van Gogh: Up Close," a retrospective covering 47 of the Dutch painter's astonishing, point-blank paintings from nature, particularly those from the last two years in Arles, Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise, France. They come from collections around the world.

Ms. Kienle argues, with Van Gogh's many letters as evidence, that the greatest Dutch painter since Rembrandt managed to survive, in part, by employing a kind of self-hypnosis, sessions of superhuman focus that helped Van Gogh put down the fires in his head.

It's not surprising that Van Gogh found transcendence in a "blade of grass"—an image he perhaps borrowed from the Calvinist critic Thomas Carlyle. And Van Gogh was not the only artist possessing a Zen-like zoom lens. Ms. Kienle might as easily have name-checked T.S. Eliot, who writes in "Four Quartets": "We must be still and still moving / Into another intensity / For a further union, a deeper communion."

More