Sunday, December 19, 2010

Paul McCartney's Tribute to John Lennon (SNL, December 11, 2010)

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

When Overlooked Art Turns Celebrity

New York Times

December 13, 2010

The painting was beautiful, just not admired. Then suddenly, after more than four centuries, it was. It acquired a pedigree. The art hadn’t changed, but its stature had.

And there it was the other day, propped on an easel in the Prado’s sunny, pristine conservation studio here, like a patient on the table in an operating theater. The most remarkable old master picture to have turned up in a long time revealed its every blemish and bruise, but also its virtues.

In September the Prado made news. It announced that this painting, “The Wine of St. Martin’s Day,” a panoramic canvas showing a mountain of revelers drinking the first wine of the season, and a few of them suffering its consequences, was by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Only 40-odd paintings by this 16th-century Flemish Renaissance master survive. This one, from around 1565, came from a private seller, whose ancient family, unaware and clearly unconcerned, had kept it for eons in the proverbial dark corridor, in Córdoba, where it accumulated dirt. Then the Prado conservators took a look. What seemed to be the artist’s signature turned up beneath layers of grime and varnish.

More

December 13, 2010

The painting was beautiful, just not admired. Then suddenly, after more than four centuries, it was. It acquired a pedigree. The art hadn’t changed, but its stature had.

And there it was the other day, propped on an easel in the Prado’s sunny, pristine conservation studio here, like a patient on the table in an operating theater. The most remarkable old master picture to have turned up in a long time revealed its every blemish and bruise, but also its virtues.

In September the Prado made news. It announced that this painting, “The Wine of St. Martin’s Day,” a panoramic canvas showing a mountain of revelers drinking the first wine of the season, and a few of them suffering its consequences, was by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Only 40-odd paintings by this 16th-century Flemish Renaissance master survive. This one, from around 1565, came from a private seller, whose ancient family, unaware and clearly unconcerned, had kept it for eons in the proverbial dark corridor, in Córdoba, where it accumulated dirt. Then the Prado conservators took a look. What seemed to be the artist’s signature turned up beneath layers of grime and varnish.

More

|

| A detail of the painting, showing a peasant celebrating during a festival for the first wine of the season. |

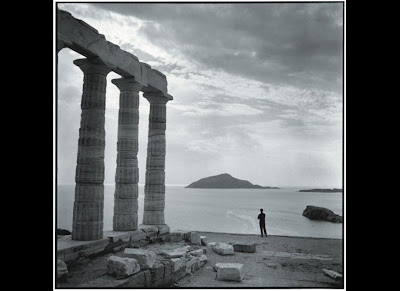

Vintage Photos from Robert McCabe's Trips to Greece in the 1950s

|

| Rhodes 1954. This marble Aphrodite, in the museum in Rhodes, was found in the sea. |

December 12, 2010

Legendary photographer Robert A. McCabe has compiled what are, in essence, stunning photographic journals of Cuba and Antarctica, among other places.

McCabe also traveled as a Princeton undergraduate to Greece in June 1954, witnessing firsthand soaring unemployment (at the time of his visit, unemployment was hovering around 30%) and poor wages (those who did work were making a little less than a dollar a day). McCabe recalls in his introduction to his book, Greece: Images of an Enchanted Land, 1954-1965, how unspoiled the landscape of Greece felt before all the tourists and development starting happening, which has forever changed the landscape in Athens.

He traveled extensively through the Aegean after that, from 1954-1965, to document fully the experiences, people and places there (he was, in particular, interested in Greece's iconic architecture).

More

|

| Sounion 1955. At the temple of Poseidon. |

|

| Epeiros 1961. Young friends. |

|

| Athens 1955. The Agora and the Acropolis from Observatory Road. |

|

| Athens 1955. Acropolis. The Propylaia from the Parthenon. |

|

| Athens 1955. The Caryatid Porch of the Erechtheion. |

|

| Serifos 1963. A church in Chora. |

|

| The Aegean 1954. On the bow of a caique. |

|

| Mykonos 1955. At a baptismal festival. |

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Saturday, November 20, 2010

The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist

by Timothy Farrington

Wall Street Journal

November 20, 2010

As a young man the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk painted seriously and dreamed of becoming a professional artist. This early passion shows in The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist, an engaging but sketchy account of the novel as an "essentially visual" literary form. Novels, the Nobel Prize winner argues, consist of "ordinary human details which are quite often visual details," strung in sequence like beads on a necklace. An author's first task is to evoke each image as precisely as possible in the reader's mind, because it is the immediacy and realism of this welter of detail that gives the novel its uniquely immersive quality.

The proper subject of the novel thus becomes, in Mr. Pamuk's view, not people's moral character but the sensibility revealed in how they react to "the manifold forms of the world—each color, each event, each fruit and blossom." The features of a character's physical and social environment, in turn, must be a "necessary extension" of their inner "emotional, sensual, and psychological world." The snowflakes that Anna Karenina watches from a train "reflect the mood of the young woman to us."

In these essays, originally presented as the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard last year, Mr. Pamuk shows himself to be at the very least an excellent reader, and his enthusiasm for his favorite novels (especially Anna Karenina but also Moby-Dick and The Magic Mountain) is winning. He also touches on the work of many earlier critics, including Nabokov, E.M. Forster and Friedrich Schiller, whose 1795 essay On Naive and Sentimental Poetry inspired his title. But Mr. Pamuk's own attempts at theory can be frustratingly vague.

More

Wall Street Journal

November 20, 2010

As a young man the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk painted seriously and dreamed of becoming a professional artist. This early passion shows in The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist, an engaging but sketchy account of the novel as an "essentially visual" literary form. Novels, the Nobel Prize winner argues, consist of "ordinary human details which are quite often visual details," strung in sequence like beads on a necklace. An author's first task is to evoke each image as precisely as possible in the reader's mind, because it is the immediacy and realism of this welter of detail that gives the novel its uniquely immersive quality.

The proper subject of the novel thus becomes, in Mr. Pamuk's view, not people's moral character but the sensibility revealed in how they react to "the manifold forms of the world—each color, each event, each fruit and blossom." The features of a character's physical and social environment, in turn, must be a "necessary extension" of their inner "emotional, sensual, and psychological world." The snowflakes that Anna Karenina watches from a train "reflect the mood of the young woman to us."

In these essays, originally presented as the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard last year, Mr. Pamuk shows himself to be at the very least an excellent reader, and his enthusiasm for his favorite novels (especially Anna Karenina but also Moby-Dick and The Magic Mountain) is winning. He also touches on the work of many earlier critics, including Nabokov, E.M. Forster and Friedrich Schiller, whose 1795 essay On Naive and Sentimental Poetry inspired his title. But Mr. Pamuk's own attempts at theory can be frustratingly vague.

More

10 Questions for Woody Allen

Time

January 17, 2008

He's brilliant at portraying neurotics of all kinds. But the multitalented director swears he's actually quite normal.

More

Also see

January 17, 2008

He's brilliant at portraying neurotics of all kinds. But the multitalented director swears he's actually quite normal.

More

Also see

The Pre-Raphaelite Lens: British Photography and Painting, 1848–1875

National Gallery of Art

October 31, 2010–January 30, 2011

A few years after the discovery of photography was announced in 1839, the British art critic John Ruskin named it "the most marvelous invention of the century." Making permanent what the eye saw fleetingly, the new technology seemed an almost magical revelation.

As photography gained a foothold in the 1840s, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. These young painters and their followers wished to return to the purity, sincerity, and clarity of detail found in medieval and early Renaissance art that preceded Raphael (1483–1520). But they were also spurred on by the possibilities of the new medium, which could capture every nuance of nature. Indeed, Pre-Raphaelite artists painted with such precision that some critics accused them of copying photographs.

Many photographers in turn looked to the language of Pre-Raphaelite painting in an effort to establish their nascent medium as a fine art. Both photographers and painters—many of whom knew one another—drew inspiration directly from nature. In choosing subjects, they also mined literature, history, and religion, as well as modern life. Together they developed a shared vocabulary that is explored in this exhibition through the genres of landscape, narrative subjects, and portraiture.

More

October 31, 2010–January 30, 2011

A few years after the discovery of photography was announced in 1839, the British art critic John Ruskin named it "the most marvelous invention of the century." Making permanent what the eye saw fleetingly, the new technology seemed an almost magical revelation.

As photography gained a foothold in the 1840s, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. These young painters and their followers wished to return to the purity, sincerity, and clarity of detail found in medieval and early Renaissance art that preceded Raphael (1483–1520). But they were also spurred on by the possibilities of the new medium, which could capture every nuance of nature. Indeed, Pre-Raphaelite artists painted with such precision that some critics accused them of copying photographs.

Many photographers in turn looked to the language of Pre-Raphaelite painting in an effort to establish their nascent medium as a fine art. Both photographers and painters—many of whom knew one another—drew inspiration directly from nature. In choosing subjects, they also mined literature, history, and religion, as well as modern life. Together they developed a shared vocabulary that is explored in this exhibition through the genres of landscape, narrative subjects, and portraiture.

More

Fantasy Not Just For the Young

by Salman Rushdie

Wall Street Journal

November 20, 2010

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking-Glass

By Lewis Carroll (1865, 1871)

The only good thing, I found, about having gone to Rugby School, the famous and wretched boys' boarding school in the British Midlands, is that Lewis Carroll went there too. The two Alice books are wonderful for children, and in some ways perhaps too good for children, full of adult wisdom and trickery. The first book, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, was initially met with dismissive notices (though John Tenniel's illustrations were well received), but it quickly became a beloved classic. What is most admirable about the second book, Through the Looking-Glass, is that it is emphatically not a return to Wonderland; Carroll's great feat is to have created two entirely discrete imagined worlds for his heroine. I have loved Alice all my life and can still recite "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter" from memory if asked to do so, or even if nobody asks.

Peter Pan

by J.M. Barrie (1911)

The Lord of the Rings

by J.R.R. Tolkien (1954-55)

The Golden Compass

by Philip Pullman (1995)

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

by Mark Haddon (2003)

More

Wall Street Journal

November 20, 2010

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking-Glass

By Lewis Carroll (1865, 1871)

The only good thing, I found, about having gone to Rugby School, the famous and wretched boys' boarding school in the British Midlands, is that Lewis Carroll went there too. The two Alice books are wonderful for children, and in some ways perhaps too good for children, full of adult wisdom and trickery. The first book, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, was initially met with dismissive notices (though John Tenniel's illustrations were well received), but it quickly became a beloved classic. What is most admirable about the second book, Through the Looking-Glass, is that it is emphatically not a return to Wonderland; Carroll's great feat is to have created two entirely discrete imagined worlds for his heroine. I have loved Alice all my life and can still recite "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter" from memory if asked to do so, or even if nobody asks.

Peter Pan

by J.M. Barrie (1911)

The Lord of the Rings

by J.R.R. Tolkien (1954-55)

The Golden Compass

by Philip Pullman (1995)

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

by Mark Haddon (2003)

More

Friday, November 19, 2010

Surprise! Jaimy Gordon Wins The National Book Award, And Patti Smith Weeps

National Public Radio

November 18, 2010

The National Book Awards are like the Oscars of literature, without the national telecast, the security guards to watch over the Harry Winston jewels or the glowing Hollywood tans (most of the nominees bear the wan, indoors-y look of the writer's life). But, like the Academy Awards, there are fancy dresses, cummerbunds and cater waiters passing around Bellinis and caviar bites — trust us, book people can party. And, much like the Oscars, the NBAs are a particular industry's biggest night, in which a career can be made (or at least pushed heartily along) with the opening of an envelope.

This year, that career belongs to Jaimy Gordon, a mid-career novelist from Baltimore living and teaching in Kalamazoo, Mich. Her fourth novel, Lord of Misrule, won the NBA for fiction on Wednesday evening, a victory that came as a surprise to many — including Gordon herself. When the announcement was read, the author's table companions shrieked at full volume, and Gordon seemed to be in shock when she finally took the stage. "I'm totally unprepared, and I’m totally surprised," she told the crowd. Later, we observed the author standing alone outside the grand façade of the Cipriani Ballroom on Wall Street in her long red gown, talking quietly into her cell phone: "I won," she said into the receiver, still seeming stunned. "I won ... the National Book Award."

Lord of Misrule, a weird, magical tale about a dusty West Virginia town and its downtrodden racetrack, follows the lives of jockeys, loan sharks, metal smiths and other outcasts over the course of a year and four horse races. The novel just arrived on shelves this month from McPherson — a small indie publisher out of Kingston, N.Y. — and while it was considered the underdog pick of the bunch, the book had already begun to gain a small momentum with critics. As Jane Smiley recently wrote in The Washington Post, "Gordon has thought so thoroughly about her characters that each voice dips into racetrack lingo in a distinctive way. It is an impressive performance."

More

November 18, 2010

The National Book Awards are like the Oscars of literature, without the national telecast, the security guards to watch over the Harry Winston jewels or the glowing Hollywood tans (most of the nominees bear the wan, indoors-y look of the writer's life). But, like the Academy Awards, there are fancy dresses, cummerbunds and cater waiters passing around Bellinis and caviar bites — trust us, book people can party. And, much like the Oscars, the NBAs are a particular industry's biggest night, in which a career can be made (or at least pushed heartily along) with the opening of an envelope.

This year, that career belongs to Jaimy Gordon, a mid-career novelist from Baltimore living and teaching in Kalamazoo, Mich. Her fourth novel, Lord of Misrule, won the NBA for fiction on Wednesday evening, a victory that came as a surprise to many — including Gordon herself. When the announcement was read, the author's table companions shrieked at full volume, and Gordon seemed to be in shock when she finally took the stage. "I'm totally unprepared, and I’m totally surprised," she told the crowd. Later, we observed the author standing alone outside the grand façade of the Cipriani Ballroom on Wall Street in her long red gown, talking quietly into her cell phone: "I won," she said into the receiver, still seeming stunned. "I won ... the National Book Award."

Lord of Misrule, a weird, magical tale about a dusty West Virginia town and its downtrodden racetrack, follows the lives of jockeys, loan sharks, metal smiths and other outcasts over the course of a year and four horse races. The novel just arrived on shelves this month from McPherson — a small indie publisher out of Kingston, N.Y. — and while it was considered the underdog pick of the bunch, the book had already begun to gain a small momentum with critics. As Jane Smiley recently wrote in The Washington Post, "Gordon has thought so thoroughly about her characters that each voice dips into racetrack lingo in a distinctive way. It is an impressive performance."

More

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Where Cinema and Biology Meet

New York Times

November 16, 2010

When Robert A. Lue considers the Star Wars Death Star, his first thought is not of outer space, but inner space.

“Luke’s initial dive into the Death Star, I’ve always thought, is a very interesting way how one would explore the surface of a cell,” he said.

That particular scene has not yet been tried, but Dr. Lue, a professor of cell biology and the director of life sciences education at Harvard, says it is one of many ideas he has for bringing visual representations of some of life’s deepest secrets to the general public.

Dr. Lue is one of the pioneers of molecular animation, a rapidly growing field that seeks to bring the power of cinema to biology. Building on decades of research and mountains of data, scientists and animators are now recreating in vivid detail the complex inner machinery of living cells.

The field has spawned a new breed of scientist-animators who not only understand molecular processes but also have mastered the computer-based tools of the film industry.

“The ability to animate really gives biologists a chance to think about things in a whole new way,” said Janet Iwasa, a cell biologist who now works as a molecular animator at Harvard Medical School.

More

November 16, 2010

When Robert A. Lue considers the Star Wars Death Star, his first thought is not of outer space, but inner space.

“Luke’s initial dive into the Death Star, I’ve always thought, is a very interesting way how one would explore the surface of a cell,” he said.

That particular scene has not yet been tried, but Dr. Lue, a professor of cell biology and the director of life sciences education at Harvard, says it is one of many ideas he has for bringing visual representations of some of life’s deepest secrets to the general public.

Dr. Lue is one of the pioneers of molecular animation, a rapidly growing field that seeks to bring the power of cinema to biology. Building on decades of research and mountains of data, scientists and animators are now recreating in vivid detail the complex inner machinery of living cells.

The field has spawned a new breed of scientist-animators who not only understand molecular processes but also have mastered the computer-based tools of the film industry.

“The ability to animate really gives biologists a chance to think about things in a whole new way,” said Janet Iwasa, a cell biologist who now works as a molecular animator at Harvard Medical School.

More

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Love and Dirty, Sexy Ducats

by Ben Brantley

New York Times

November 13, 2010

They belong to worlds that, in the normal course of events, would never intersect. But Shakespeare, as the creator of their universe, saw fit to let their paths cross just once. And when Portia finally meets Shylock, in Daniel Sullivan’s absolutely splendid production of The Merchant of Venice at the Broadhurst Theater, the collision lights up the sky.

Giving what promise to be the performances of this season, Lily Rabe, as Portia the heiress, and Al Pacino, as Shylock the usurer, invest the much-parsed trial scene of this fascinating, irksome work with a passion and an anger that purge it of preconceptions. You may find yourself trembling, as one often does when something scary and baffling starts to make sense. At the same time you’re likely to have trouble figuring out exactly where your sympathies lie. For at this moment everybody hurts.

In traditional presentations of Act IV, Scene 1 of “Merchant” Portia, disguised as a male lawyer to rescue a man under threat of death, emerges as an avenging angel; Shylock, viciously poised to kill an enemy in an act of legal redress, is usually the vanquished villain or, in more fashionable contemporary readings, the Jewish victim of a Christian social order reasserting itself.

But what you read in Ms. Rabe’s delicately expressive features is hardly a look of triumph. Her face is that of someone registering a precious and irrevocable loss. In an odd way the fatalistic, shrunken sorrow of Mr. Pacino’s crouched Shylock, who has not only been thwarted of his revenge but also stripped of his identity, seems to mirror Portia’s own state of mind.

More

New York Times

November 13, 2010

They belong to worlds that, in the normal course of events, would never intersect. But Shakespeare, as the creator of their universe, saw fit to let their paths cross just once. And when Portia finally meets Shylock, in Daniel Sullivan’s absolutely splendid production of The Merchant of Venice at the Broadhurst Theater, the collision lights up the sky.

Giving what promise to be the performances of this season, Lily Rabe, as Portia the heiress, and Al Pacino, as Shylock the usurer, invest the much-parsed trial scene of this fascinating, irksome work with a passion and an anger that purge it of preconceptions. You may find yourself trembling, as one often does when something scary and baffling starts to make sense. At the same time you’re likely to have trouble figuring out exactly where your sympathies lie. For at this moment everybody hurts.

In traditional presentations of Act IV, Scene 1 of “Merchant” Portia, disguised as a male lawyer to rescue a man under threat of death, emerges as an avenging angel; Shylock, viciously poised to kill an enemy in an act of legal redress, is usually the vanquished villain or, in more fashionable contemporary readings, the Jewish victim of a Christian social order reasserting itself.

But what you read in Ms. Rabe’s delicately expressive features is hardly a look of triumph. Her face is that of someone registering a precious and irrevocable loss. In an odd way the fatalistic, shrunken sorrow of Mr. Pacino’s crouched Shylock, who has not only been thwarted of his revenge but also stripped of his identity, seems to mirror Portia’s own state of mind.

More

Friday, November 12, 2010

As Complex as the Music She Plays

New York Times

November 11, 2010

It seems safe to predict that the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter will play a run of concerts with the New York Philharmonic in 10 years or so, as she did in 2000 and as she is doing again this season, as artist in residence. After all, unless she were finally to act on occasional vague hints of an early retirement, Ms. Mutter, now 47, should still be at the height of her considerable powers.

What is harder to predict is what she might play. If she follows form, she will present several pieces that have yet to be written. In 2000 she played only 20th-century music, including newish works by Witold Lutoslawski, Krzysztof Penderecki and Wolfgang Rihm. Now, in three orchestral programs and in assorted chamber concerts, she is adding four new works — two by Mr. Rihm, one each by Mr. Penderecki and Sebastian Currier — to the 14 world premieres she has listed on her own Web site and giving the New York premiere of Sofia Gubaidulina’s “In Tempus Praesens” (2007), also written for her.

More

November 11, 2010

It seems safe to predict that the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter will play a run of concerts with the New York Philharmonic in 10 years or so, as she did in 2000 and as she is doing again this season, as artist in residence. After all, unless she were finally to act on occasional vague hints of an early retirement, Ms. Mutter, now 47, should still be at the height of her considerable powers.

What is harder to predict is what she might play. If she follows form, she will present several pieces that have yet to be written. In 2000 she played only 20th-century music, including newish works by Witold Lutoslawski, Krzysztof Penderecki and Wolfgang Rihm. Now, in three orchestral programs and in assorted chamber concerts, she is adding four new works — two by Mr. Rihm, one each by Mr. Penderecki and Sebastian Currier — to the 14 world premieres she has listed on her own Web site and giving the New York premiere of Sofia Gubaidulina’s “In Tempus Praesens” (2007), also written for her.

More

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

My Endless New York

by Tony Judt

New York Times

November 7, 2010

I came to New York University in 1987 on a whim. The Thatcherite assault on British higher education was just beginning and even in Oxford the prospects were grim. N.Y.U. appealed to me: by no means a recent foundation — it was established in 1831 — it is nevertheless the junior of New York City’s great universities. Less of a “city on a hill,” it is more open to new directions: in contrast to the cloistered collegiate worlds of Oxbridge, it brazenly advertises itself as a “global” university at the heart of a world city.

But just what is a “world city”? Mexico City, at 18 million people, or São Paulo at near that, are unmanageable urban sprawls; they are not “world cities.” Conversely, Paris — whose central districts have never exceeded three million inhabitants — was the capital of the 19th century.

Is it a function of the number of visitors? In that case, Orlando, Fla., would be a great metropolis. Being the capital of a country guarantees nothing: think of Madrid or Washington (the Brasília of its time). It may not even be a matter of wealth: within the foreseeable future Shanghai (14 million people) will surely be among the richest places on earth; Singapore already is. Will they be “world cities”?

I have lived in four such cities. London was the commercial and financial center of the world from the defeat of Napoleon until the rise of Hitler; Paris, its perennial competitor, was an international cultural magnet from the building of Versailles through the death of Albert Camus. Vienna’s apogee was perhaps the shortest: its rise and fall coincided with the last years of the Hapsburg Empire, though in intensity it outshone them all. And then came New York.

More

New York Times

November 7, 2010

I came to New York University in 1987 on a whim. The Thatcherite assault on British higher education was just beginning and even in Oxford the prospects were grim. N.Y.U. appealed to me: by no means a recent foundation — it was established in 1831 — it is nevertheless the junior of New York City’s great universities. Less of a “city on a hill,” it is more open to new directions: in contrast to the cloistered collegiate worlds of Oxbridge, it brazenly advertises itself as a “global” university at the heart of a world city.

But just what is a “world city”? Mexico City, at 18 million people, or São Paulo at near that, are unmanageable urban sprawls; they are not “world cities.” Conversely, Paris — whose central districts have never exceeded three million inhabitants — was the capital of the 19th century.

Is it a function of the number of visitors? In that case, Orlando, Fla., would be a great metropolis. Being the capital of a country guarantees nothing: think of Madrid or Washington (the Brasília of its time). It may not even be a matter of wealth: within the foreseeable future Shanghai (14 million people) will surely be among the richest places on earth; Singapore already is. Will they be “world cities”?

I have lived in four such cities. London was the commercial and financial center of the world from the defeat of Napoleon until the rise of Hitler; Paris, its perennial competitor, was an international cultural magnet from the building of Versailles through the death of Albert Camus. Vienna’s apogee was perhaps the shortest: its rise and fall coincided with the last years of the Hapsburg Empire, though in intensity it outshone them all. And then came New York.

More

Monday, November 8, 2010

Being There: Berlin

by Jonathan Rosenthal

Intelligent Life

Autumn 2010

Every city has its history. Some, such as Paris, revel in theirs, while others—London comes to mind—draw gravitas from it. My home town of Johannesburg, which could be weighed down by its history, wears it lightly. And some cities just have too much: Berlin is one of them.

It was because of some of this history that my family fled Germany two generations ago. Our branch of the family was lucky. My grandfather, who lived in a village outside Frankfurt called Gedern, had a run-in with a local Nazi which turned violent. Family lore has it that he left town that night with his parents and brothers. Aunts, uncles and cousins stayed, and few of them survived the Holocaust.

It was a history that followed him to our dinner table in South Africa like a brooding relative who suddenly speaks up in the middle of a meal. Grandpa Ludwig’s fierce temper was supposedly a German trait; my father’s square head was called a “Krautkopf”. And there was bitterness. My father visited Germany just once in the early 1960s and couldn’t stand to stay more than one night. Whenever he looked at men his father’s age, he wanted to ask what they had done during the war. Had he stayed a little longer, he would have found many Germans his age asking similar questions of their parents.

Many still do. History in these parts is not neatly layered like a German chocolate cake: it is all jumbled up, so the past is always present. Berlin’s new business school is housed in the cathedral to communism that was built for East Germany’s rulers in 1964, so blond hammer-wielding workers and athletic, short-skirted women smile down from huge stained-glass windows on bank executives and MBA students debating the intricacies of corporate finance. The national treasury is inside a building that was first built as Hermann Goering’s air ministry, then used by the Soviet army, and later by the East German government.

More

Intelligent Life

Autumn 2010

Every city has its history. Some, such as Paris, revel in theirs, while others—London comes to mind—draw gravitas from it. My home town of Johannesburg, which could be weighed down by its history, wears it lightly. And some cities just have too much: Berlin is one of them.

It was because of some of this history that my family fled Germany two generations ago. Our branch of the family was lucky. My grandfather, who lived in a village outside Frankfurt called Gedern, had a run-in with a local Nazi which turned violent. Family lore has it that he left town that night with his parents and brothers. Aunts, uncles and cousins stayed, and few of them survived the Holocaust.

It was a history that followed him to our dinner table in South Africa like a brooding relative who suddenly speaks up in the middle of a meal. Grandpa Ludwig’s fierce temper was supposedly a German trait; my father’s square head was called a “Krautkopf”. And there was bitterness. My father visited Germany just once in the early 1960s and couldn’t stand to stay more than one night. Whenever he looked at men his father’s age, he wanted to ask what they had done during the war. Had he stayed a little longer, he would have found many Germans his age asking similar questions of their parents.

Many still do. History in these parts is not neatly layered like a German chocolate cake: it is all jumbled up, so the past is always present. Berlin’s new business school is housed in the cathedral to communism that was built for East Germany’s rulers in 1964, so blond hammer-wielding workers and athletic, short-skirted women smile down from huge stained-glass windows on bank executives and MBA students debating the intricacies of corporate finance. The national treasury is inside a building that was first built as Hermann Goering’s air ministry, then used by the Soviet army, and later by the East German government.

More

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Jill Clayburgh (1944–2010)

An Unmarried Woman (1978)

written and directed by Paul Mazursky

Clayburgh’s Unforgettable Unmarried Woman (Washington Post, November 7, 2010)

written and directed by Paul Mazursky

Clayburgh’s Unforgettable Unmarried Woman (Washington Post, November 7, 2010)

Friday, November 5, 2010

The Spanish Manner: Drawings from Ribera to Goya

Inspired by the technical and aesthetic achievements of Italy and Flanders, Spanish draftsmen in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries created works that continue to impress modern viewers. This online exhibition was designed to complement an in situ exhibit at the Frick Museum in New York, and it features works by Goya, Ribera, and Murillo. On this site, visitors can look over introductory essays on the exhibit and read over a nice piece on the emotional and artistic content of works by Goya. Moving on, the "Podcasts" area contains several podcasts, including a conversation with curators to discuss several key works in the exhibition. The site is rounded out by an exhibition checklist which allows users to view the various works here.

More

Source (The Scout Report)

More

Source (The Scout Report)

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Pacino Wants to Be Fair to Shakespeare

New York Times

October 29, 2010

Some stars get their names above the title. Others’ appear in lights on the marquee. Then there’s Al Pacino. A giant photo of his weary-looking face in the new production of The Merchant of Venice towers above West 44th Street, high above signs for Phantom of the Opera and American Idiot. The Public Theater production of Merchant, staged by Daniel Sullivan at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, received glowing reviews last summer, but this simple, unadorned portrait explains why the show is transferring to Broadway at the Broadhurst Theater: star power, pure and simple. And, sure enough, ticket sales have already been brisk.

Down below the portrait, Mr. Pacino, wearing rumpled clothes and a tangled mop of hair, walked out the stage door recently and across the street to Sardi’s, where he set up in his usual corner table and ordered a shrimp cocktail. His deep-set eyes and raspy laugh were familiar, but in some of his flat vowels and musical stammer you could detect his distinctive performance as a vengeful, proud Shylock. Mr. Pacino, who turned 70 this year, talked with Jason Zinoman about his career, his craft and a lifetime of Shakespeare, although he deflected many questions about Shylock, which he said he preferred to avoid looking at from a critical distance.

At several moments, when pressed about what he was thinking, he turned quiet. Then he’d pivot and fly in a new direction: “Marlon Brando said a great thing once,” he said interrupting one such interval. “In movies, when they say, ‘Action,’ you don’t have to do it. I like that.”

More

Read the review by Ben Brantley (NYT, June 30, 2010)

See a video from the theatrical performance

October 29, 2010

Some stars get their names above the title. Others’ appear in lights on the marquee. Then there’s Al Pacino. A giant photo of his weary-looking face in the new production of The Merchant of Venice towers above West 44th Street, high above signs for Phantom of the Opera and American Idiot. The Public Theater production of Merchant, staged by Daniel Sullivan at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, received glowing reviews last summer, but this simple, unadorned portrait explains why the show is transferring to Broadway at the Broadhurst Theater: star power, pure and simple. And, sure enough, ticket sales have already been brisk.

Down below the portrait, Mr. Pacino, wearing rumpled clothes and a tangled mop of hair, walked out the stage door recently and across the street to Sardi’s, where he set up in his usual corner table and ordered a shrimp cocktail. His deep-set eyes and raspy laugh were familiar, but in some of his flat vowels and musical stammer you could detect his distinctive performance as a vengeful, proud Shylock. Mr. Pacino, who turned 70 this year, talked with Jason Zinoman about his career, his craft and a lifetime of Shakespeare, although he deflected many questions about Shylock, which he said he preferred to avoid looking at from a critical distance.

At several moments, when pressed about what he was thinking, he turned quiet. Then he’d pivot and fly in a new direction: “Marlon Brando said a great thing once,” he said interrupting one such interval. “In movies, when they say, ‘Action,’ you don’t have to do it. I like that.”

More

Read the review by Ben Brantley (NYT, June 30, 2010)

See a video from the theatrical performance

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Joan Sutherland, Flawless Soprano, Is Dead at 83

by Anthony Tommasini

New York Times

October 11, 2010

Joan Sutherland, one of the most acclaimed sopranos of the 20th century, a singer of such power and range that she was crowned “La Stupenda,” died on Sunday at her home in Switzerland, near Montreux. She was 83.

Her death was confirmed by her close friend the mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne.

It was Italy’s notoriously picky critics who dubbed the Australian-born Ms. Sutherland the Stupendous One after her Italian debut, in Venice in 1960. And for 40 years the name endured with opera lovers around the world. Her 1961 debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, generated so much excitement that standees began lining up at 7:30 that morning. Her singing of the Mad Scene drew a thunderous 12-minute ovation.

More

New York Times

October 11, 2010

Joan Sutherland, one of the most acclaimed sopranos of the 20th century, a singer of such power and range that she was crowned “La Stupenda,” died on Sunday at her home in Switzerland, near Montreux. She was 83.

Her death was confirmed by her close friend the mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne.

It was Italy’s notoriously picky critics who dubbed the Australian-born Ms. Sutherland the Stupendous One after her Italian debut, in Venice in 1960. And for 40 years the name endured with opera lovers around the world. Her 1961 debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, generated so much excitement that standees began lining up at 7:30 that morning. Her singing of the Mad Scene drew a thunderous 12-minute ovation.

More

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Why Literature?

by Mario Vargas Llosa

New Republic

May 14, 2001

It has often happened to me, at book fairs or in bookstores, that a gentleman approaches me and asks me for a signature. "It is for my wife, my young daughter, or my mother," he explains. "She is a great reader and loves literature." Immediately I ask: "And what about you? Don't you like to read?" The answer is almost always the same: "Of course I like to read, but I am a very busy person." I have heard this explanation dozens of times: this man and many thousands of men like him have so many important things to do, so many obligations, so many responsibilities in life, that they cannot waste their precious time buried in a novel, a book of poetry, or a literary essay for hours and hours. According to this widespread conception, literature is a dispensable activity, no doubt lofty and useful for cultivating sensitivity and good manners, but essentially an entertainment, an adornment that only people with time for recreation can afford. It is something to fit in between sports, the movies, a game of bridge or chess; and it can be sacrificed without scruple when one "prioritizes" the tasks and the duties that are indispensable in the struggle of life.

It seems clear that literature has become more and more a female activity. In bookstores, at conferences or public readings by writers, and even in university departments dedicated to the humanities, the women clearly outnumber the men. The explanation traditionally given is that middle-class women read more because they work fewer hours than men, and so many of them feel that they can justify more easily than men the time that they devote to fantasy and illusion. I am somewhat allergic to explanations that divide men and women into frozen categories and attribute to each sex its characteristic virtues and shortcomings; but there is no doubt that there are fewer and fewer readers of literature, and that among the saving remnant of readers women predominate.

More

New Republic

May 14, 2001

It has often happened to me, at book fairs or in bookstores, that a gentleman approaches me and asks me for a signature. "It is for my wife, my young daughter, or my mother," he explains. "She is a great reader and loves literature." Immediately I ask: "And what about you? Don't you like to read?" The answer is almost always the same: "Of course I like to read, but I am a very busy person." I have heard this explanation dozens of times: this man and many thousands of men like him have so many important things to do, so many obligations, so many responsibilities in life, that they cannot waste their precious time buried in a novel, a book of poetry, or a literary essay for hours and hours. According to this widespread conception, literature is a dispensable activity, no doubt lofty and useful for cultivating sensitivity and good manners, but essentially an entertainment, an adornment that only people with time for recreation can afford. It is something to fit in between sports, the movies, a game of bridge or chess; and it can be sacrificed without scruple when one "prioritizes" the tasks and the duties that are indispensable in the struggle of life.

It seems clear that literature has become more and more a female activity. In bookstores, at conferences or public readings by writers, and even in university departments dedicated to the humanities, the women clearly outnumber the men. The explanation traditionally given is that middle-class women read more because they work fewer hours than men, and so many of them feel that they can justify more easily than men the time that they devote to fantasy and illusion. I am somewhat allergic to explanations that divide men and women into frozen categories and attribute to each sex its characteristic virtues and shortcomings; but there is no doubt that there are fewer and fewer readers of literature, and that among the saving remnant of readers women predominate.

More

Friday, October 8, 2010

A universal Peruvian

Economist

October 7, 2010

It had seemed inevitable that Mario Vargas Llosa was condemned to join the list of great writers never to receive the Nobel prize, while many of lesser talent but more fashionable views were honoured. So this year’s award is welcome, if overdue, recognition for the most accomplished living Latin American novelist and writer.

In its citation, the committee commends Mr Vargas Llosa for “his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.” These themes are treated most powerfully in what are perhaps his two finest novels, written more than three decades apart. Conversation in the Cathedral, an early work of astonishing maturity, is set in Peru in the 1950s during a military dictatorship. The Feast of the Goat, published in 2000, explores the cruel regime of General Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. While novels about dictators are a staple of Latin American literature, Mr Vargas Llosa took the genre beyond political denunciation, crafting subtle studies of the psychology of absolute power and its corruption of human integrity. These are themes he returns to in his latest book, El Sueño del Celta (The Dream of the Celt), a novel about Roger Casement, an Anglo-Irish diplomat and early crusader for human rights, which will be published in Spanish in November.

More

October 7, 2010

It had seemed inevitable that Mario Vargas Llosa was condemned to join the list of great writers never to receive the Nobel prize, while many of lesser talent but more fashionable views were honoured. So this year’s award is welcome, if overdue, recognition for the most accomplished living Latin American novelist and writer.

In its citation, the committee commends Mr Vargas Llosa for “his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.” These themes are treated most powerfully in what are perhaps his two finest novels, written more than three decades apart. Conversation in the Cathedral, an early work of astonishing maturity, is set in Peru in the 1950s during a military dictatorship. The Feast of the Goat, published in 2000, explores the cruel regime of General Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. While novels about dictators are a staple of Latin American literature, Mr Vargas Llosa took the genre beyond political denunciation, crafting subtle studies of the psychology of absolute power and its corruption of human integrity. These are themes he returns to in his latest book, El Sueño del Celta (The Dream of the Celt), a novel about Roger Casement, an Anglo-Irish diplomat and early crusader for human rights, which will be published in Spanish in November.

More

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Mario Vargas Llosa Wins Nobel Literature Prize

Associated Press/New York Times

October 7, 2010

Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the most acclaimed writers in the Spanish-speaking world who once ran for president in his homeland, won the 2010 Nobel Prize in literature on Thursday.

The Swedish Academy said it honored the 74-year-old author "for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual's resistance, revolt and defeat."

Vargas Llosa has written more than 30 novels, plays and essays, including Conversation in the Cathedral and The Green House. In 1995, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the Spanish-speaking world's most distinguished literary honor.

His international breakthrough came with the 1960s novel The Time of The Hero, which builds on his experiences from the Peruvian military academy Leoncio Prado. The book was considered controversial in his homeland and a thousand copies were burnt publicly by officers from the academy.

Vargas Llosa is the first South American winner of the prestigious 10 million kronor ($1.5 million) Nobel Prize in literature since it was awarded to Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez in 1982.

In the previous six years, the academy rewarded five Europeans and one Turk, sparking criticism that it was too euro-centric.

Born in Arequipa, Peru, Vargas Llosa grew up with his grandparents in Bolivia after his parents divorced, the academy said. The family moved back to Peru in 1946 and he later went to military school before studying literature and law in Lima and Madrid.

In 1959, he moved to Paris where he worked as a language teacher and as a journalist for Agence France-Presse and the national television service of France.

He has lectured and taught at a number of universities in the U.S., South America and Europe. He is teaching this semester at Princeton University in Princeton, N.J.

In 1990, he ran for the presidency but lost the election to Alberto Fujimori. In 1994 he was elected to the Spanish Academy, where he took his seat in 1996.

More

Winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature (NYT)

Official Website of the Nobel Prize

October 7, 2010

Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the most acclaimed writers in the Spanish-speaking world who once ran for president in his homeland, won the 2010 Nobel Prize in literature on Thursday.

The Swedish Academy said it honored the 74-year-old author "for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual's resistance, revolt and defeat."

Vargas Llosa has written more than 30 novels, plays and essays, including Conversation in the Cathedral and The Green House. In 1995, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the Spanish-speaking world's most distinguished literary honor.

His international breakthrough came with the 1960s novel The Time of The Hero, which builds on his experiences from the Peruvian military academy Leoncio Prado. The book was considered controversial in his homeland and a thousand copies were burnt publicly by officers from the academy.

Vargas Llosa is the first South American winner of the prestigious 10 million kronor ($1.5 million) Nobel Prize in literature since it was awarded to Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez in 1982.

In the previous six years, the academy rewarded five Europeans and one Turk, sparking criticism that it was too euro-centric.

Born in Arequipa, Peru, Vargas Llosa grew up with his grandparents in Bolivia after his parents divorced, the academy said. The family moved back to Peru in 1946 and he later went to military school before studying literature and law in Lima and Madrid.

In 1959, he moved to Paris where he worked as a language teacher and as a journalist for Agence France-Presse and the national television service of France.

He has lectured and taught at a number of universities in the U.S., South America and Europe. He is teaching this semester at Princeton University in Princeton, N.J.

In 1990, he ran for the presidency but lost the election to Alberto Fujimori. In 1994 he was elected to the Spanish Academy, where he took his seat in 1996.

More

Winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature (NYT)

Official Website of the Nobel Prize

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Jonathan Franzen: 'I must be near the end of my career – people are starting to approve'

Interview to Ed Pilkington

Guardian

September 25, 2010

Last month, Jonathan Franzen became the first author in a decade to appear on the cover of Time magazine. Over a shot of him looking characteristically serious appeared the words "Great American Novelist".

In his famous Harper's essay of 1996, Franzen had bemoaned the magazine's lack of literary pin-ups as evidence of the declining importance of serious fiction, so you might think he'd be in celebratory mood. Being Franzen, he isn't comfortable with the label. "It paints a big bullseye on the back of my head," he says. "I always hated the expression anyway, mostly because I encountered it in stupid or sneering contexts."

He switches to a high-pitched mocking tone: "Still working on the Great American Novel?" Then adopts the barrel voice of a dunce: "I'm thinking of taking a year off to go to France and write a Great American Novel."

The sneering began after Franzen expressed misgivings over the selection of his last novel, The Corrections, for the Oprah Winfrey book club, in 2001. It sold nearly 3m copies and established Franzen as one of the leading literary voices of his generation, but, thanks to his perceived snub to Winfrey, it also established his reputation as, variously, an "ego-blinded snob" (Boston Globe), a "pompous prick" (Newsweek) and a "spoiled, whiny little brat" (Chicago Tribune).

The fallout set back his writing by more than a year. This time, Franzen has toughened up. "Whatever happens," he says, of his new novel Freedom, "it's not going to get to me. It's just not."

More

Guardian

September 25, 2010

Last month, Jonathan Franzen became the first author in a decade to appear on the cover of Time magazine. Over a shot of him looking characteristically serious appeared the words "Great American Novelist".

In his famous Harper's essay of 1996, Franzen had bemoaned the magazine's lack of literary pin-ups as evidence of the declining importance of serious fiction, so you might think he'd be in celebratory mood. Being Franzen, he isn't comfortable with the label. "It paints a big bullseye on the back of my head," he says. "I always hated the expression anyway, mostly because I encountered it in stupid or sneering contexts."

He switches to a high-pitched mocking tone: "Still working on the Great American Novel?" Then adopts the barrel voice of a dunce: "I'm thinking of taking a year off to go to France and write a Great American Novel."

The sneering began after Franzen expressed misgivings over the selection of his last novel, The Corrections, for the Oprah Winfrey book club, in 2001. It sold nearly 3m copies and established Franzen as one of the leading literary voices of his generation, but, thanks to his perceived snub to Winfrey, it also established his reputation as, variously, an "ego-blinded snob" (Boston Globe), a "pompous prick" (Newsweek) and a "spoiled, whiny little brat" (Chicago Tribune).

The fallout set back his writing by more than a year. This time, Franzen has toughened up. "Whatever happens," he says, of his new novel Freedom, "it's not going to get to me. It's just not."

More

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Still Loving You - Scorpions with The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (2000)

Saturday, September 18, 2010

Why I Hate Ordering Wine by the Glass

by Lettie Teague

Wall Street Journal

September 18, 2010

Every wine drinker I know maintains at least one wine-related prejudice or another—whether he admits it or not. One friend, for example, abhors drinking white wine while another eschews all rosés (he has labeled them "Pepto de Provence.") Yet a third disdains Riesling on account of the bottle, which she calls a "needle nose." (She's a former fashion editor—of course.)

I have a wine prejudice of my own: I simply hate wines by the glass. But unlike most prejudices, born of ignorance and fear, my prejudice was acquired through experience.

Foremost among my glass-hating reasons is price. Wines by the glass are almost invariably the worst deal in the house. After all, the conventional rule of thumb calls for the price of the glass to equal the wholesale cost of the bottle, plus, often, a few dollars more. And with five glasses in a bottle (or four, at a more conservative measure) that's a profit margin so large that only the greediest restaurateurs would dare to charge a similar markup on a full bottle. As Michael Madrigale, wine director of New York's Bar Boulud, put it: "The wine-by-the-glass program pays for corked bottles and when wine gets sent back. For most wine directors, it's the profit engine of a wine list."

More

Wall Street Journal

September 18, 2010

Every wine drinker I know maintains at least one wine-related prejudice or another—whether he admits it or not. One friend, for example, abhors drinking white wine while another eschews all rosés (he has labeled them "Pepto de Provence.") Yet a third disdains Riesling on account of the bottle, which she calls a "needle nose." (She's a former fashion editor—of course.)

I have a wine prejudice of my own: I simply hate wines by the glass. But unlike most prejudices, born of ignorance and fear, my prejudice was acquired through experience.

Foremost among my glass-hating reasons is price. Wines by the glass are almost invariably the worst deal in the house. After all, the conventional rule of thumb calls for the price of the glass to equal the wholesale cost of the bottle, plus, often, a few dollars more. And with five glasses in a bottle (or four, at a more conservative measure) that's a profit margin so large that only the greediest restaurateurs would dare to charge a similar markup on a full bottle. As Michael Madrigale, wine director of New York's Bar Boulud, put it: "The wine-by-the-glass program pays for corked bottles and when wine gets sent back. For most wine directors, it's the profit engine of a wine list."

More

Forget What You Know of Twain, Then Delight in Your Rediscovery

New York Times

September 17, 2010

Mark Twain’s heroes tend to land in unexpected places: caves, locked cabins, long-gone eras, the Czar’s palace, a Tasmanian jungle, Southern drawing rooms. Whether it’s Huck Finn floating on a raft with an escaped slave or Hank Morgan thrust into the court of King Arthur, they are generally good-humored about their quandary and come out in pretty decent condition, tossing off a few wisecracks, learning a few things, maybe even making a fortune.

But puzzling it all out isn’t easy: how do you make sense of an alien or changing world? Can you make judgments based on what you’ve been taught or what you think you already know, whether as prince or pauper? People are different there: what are we to make of them? How are we to act?

But puzzling it all out isn’t easy: how do you make sense of an alien or changing world? Can you make judgments based on what you’ve been taught or what you think you already know, whether as prince or pauper? People are different there: what are we to make of them? How are we to act?

Samuel Clemens, of course, must have often felt the same way, his 74-year life arcing from rural poverty to world renown, from the antebellum South to 20th-century industrial New England, from Confederate sympathies to the rationalist skepticism of liberal modernity. He created a persona so familiar to us, so amiably congenial and sardonic, at once so folksy and high-toned with its attempt to cudgel and cajole the sense out of things, that we may think we understand him too. He landed squarely on his feet late in life, a modern man. And 100 years after his death and 175 after his birth, he still comfortably stands in our company. But in this year of dual birth and death commemorations, go to the Morgan Library & Museum, where a major new exhibition, Mark Twain: A Skeptic’s Progress, draws from two great collections of books and manuscripts at the Morgan and the New York Public Library.

Περισσότερα

September 17, 2010

Mark Twain’s heroes tend to land in unexpected places: caves, locked cabins, long-gone eras, the Czar’s palace, a Tasmanian jungle, Southern drawing rooms. Whether it’s Huck Finn floating on a raft with an escaped slave or Hank Morgan thrust into the court of King Arthur, they are generally good-humored about their quandary and come out in pretty decent condition, tossing off a few wisecracks, learning a few things, maybe even making a fortune.

But puzzling it all out isn’t easy: how do you make sense of an alien or changing world? Can you make judgments based on what you’ve been taught or what you think you already know, whether as prince or pauper? People are different there: what are we to make of them? How are we to act?

But puzzling it all out isn’t easy: how do you make sense of an alien or changing world? Can you make judgments based on what you’ve been taught or what you think you already know, whether as prince or pauper? People are different there: what are we to make of them? How are we to act?Samuel Clemens, of course, must have often felt the same way, his 74-year life arcing from rural poverty to world renown, from the antebellum South to 20th-century industrial New England, from Confederate sympathies to the rationalist skepticism of liberal modernity. He created a persona so familiar to us, so amiably congenial and sardonic, at once so folksy and high-toned with its attempt to cudgel and cajole the sense out of things, that we may think we understand him too. He landed squarely on his feet late in life, a modern man. And 100 years after his death and 175 after his birth, he still comfortably stands in our company. But in this year of dual birth and death commemorations, go to the Morgan Library & Museum, where a major new exhibition, Mark Twain: A Skeptic’s Progress, draws from two great collections of books and manuscripts at the Morgan and the New York Public Library.

Περισσότερα

Friday, September 17, 2010

Guggenheim: Interact

The Scout Report

September 17, 2010

Interacting with the Guggenheim museums' collections is a great experience, and if you can't make it to one of their physical locations, this is the next best thing. The site is replete with creative assemblages of video ("YouTube Play"), blogs ("The Take"), and electronic newsletter options. Visitors shouldn't miss the "Voices from the Archives" area. Here they can listen to recent podcasts and as well as events from the past, including a conversation with Kandinsky scholar Rose-Carol Washton Long from 1964. Perhaps the most interesting part of the site is the "Declarations" section. Here, the Guggenheim has invited a "wide range of artists, scholars, activists, businesspeople, and government leaders to contribute concise remarks on related topical themes." One of the recent queries was "How is the idea of progress part of your practice?", and the responses are quite revealing. Finally, visitors can also make their way through their scrolling Twitter feed, and they are also encouraged to use the social media connections on the site to stay up-to-date.

More

September 17, 2010

Interacting with the Guggenheim museums' collections is a great experience, and if you can't make it to one of their physical locations, this is the next best thing. The site is replete with creative assemblages of video ("YouTube Play"), blogs ("The Take"), and electronic newsletter options. Visitors shouldn't miss the "Voices from the Archives" area. Here they can listen to recent podcasts and as well as events from the past, including a conversation with Kandinsky scholar Rose-Carol Washton Long from 1964. Perhaps the most interesting part of the site is the "Declarations" section. Here, the Guggenheim has invited a "wide range of artists, scholars, activists, businesspeople, and government leaders to contribute concise remarks on related topical themes." One of the recent queries was "How is the idea of progress part of your practice?", and the responses are quite revealing. Finally, visitors can also make their way through their scrolling Twitter feed, and they are also encouraged to use the social media connections on the site to stay up-to-date.

More

They Had Great Character

by Stephen Tobolowsky

New York Times

September 16, 2010

One evening not long ago, my wife and I were standing in the lobby of a theater when a group of women approached me with “that look.” It’s a look that I have come to know as the “You are either someone in show business or my former chiropractor” look.

The women smiled bashfully and the brave one asked, “Are you who we think you are?” I responded, fearful of litigation, “That all depends on who you think I am.”

She giggled and said, “The actor.” I bowed and replied, “Yes, ma’am.” She brightened: “The one on ‘Lost.’”

I said, “No, no, sorry.”

Undeterred, she followed up with, “No, I meant the movie by the Coen brothers, ‘A Serious Man.’ ”

I was not in that movie either, though I auditioned for it and offered to wash Joel and Ethan’s cars if they would cast me. I suggested to the women that they had seen me in “Groundhog Day” or “Glee,” neither of which they had heard of. At this point I was certain that I had to be talking to visitors from another world or time travelers.

This is an encounter that I have had quite often. I am a character actor: the perfect combination of ubiquity and anonymity. But this particular comedy of errors made me give some serious thought to the strange, occasionally delightful and often humbling path we character actors tread. My thoughts were tinged with the sadness of having recently lost five magnificent companions on that road — Kevin McCarthy, Carl Gordon, Maury Chaykin, James Gammon and Harold Gould.

More

New York Times

September 16, 2010

One evening not long ago, my wife and I were standing in the lobby of a theater when a group of women approached me with “that look.” It’s a look that I have come to know as the “You are either someone in show business or my former chiropractor” look.

The women smiled bashfully and the brave one asked, “Are you who we think you are?” I responded, fearful of litigation, “That all depends on who you think I am.”

She giggled and said, “The actor.” I bowed and replied, “Yes, ma’am.” She brightened: “The one on ‘Lost.’”

I said, “No, no, sorry.”

Undeterred, she followed up with, “No, I meant the movie by the Coen brothers, ‘A Serious Man.’ ”

I was not in that movie either, though I auditioned for it and offered to wash Joel and Ethan’s cars if they would cast me. I suggested to the women that they had seen me in “Groundhog Day” or “Glee,” neither of which they had heard of. At this point I was certain that I had to be talking to visitors from another world or time travelers.

This is an encounter that I have had quite often. I am a character actor: the perfect combination of ubiquity and anonymity. But this particular comedy of errors made me give some serious thought to the strange, occasionally delightful and often humbling path we character actors tread. My thoughts were tinged with the sadness of having recently lost five magnificent companions on that road — Kevin McCarthy, Carl Gordon, Maury Chaykin, James Gammon and Harold Gould.

More

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Woody Allen on Faith, Fortune Tellers and New York

by Dave Itzkoff

New York Times

September 14, 2010

Asked on Tuesday morning if it was appropriate to wish him a happy Jewish New Year, Woody Allen made it clear that such formalities were not necessary. “No, no, no,” he said with a chuckle, seated in an office suite at the Loews Regency hotel. “That’s for your people,” he told this reporter. “I don’t follow it. I wish I could get with it. It would be a big help on those dark nights.”

At 74, Mr. Allen, the prolific filmmaker and emblematic New Yorker, has hardly found religion. But the idea of faith informs his latest movie, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, which Sony Pictures Classics is to release next Wednesday. In the film, as the marriage of a London couple (Anthony Hopkins and Gemma Jones) unravels, the wife seeks comfort in the supernatural, which has unforeseen consequences on the marriage of her daughter (Naomi Watts) and her husband (Josh Brolin).

“To me,” Mr. Allen said, “there’s no real difference between a fortune teller or a fortune cookie and any of the organized religions. They’re all equally valid or invalid, really. And equally helpful.”

Mr. Allen spoke with Dave Itzkoff about his new film, how its themes resonate in his life and whether he has made his last movie in New York. These are excerpts from that conversation.

More

New York Times

September 14, 2010

Asked on Tuesday morning if it was appropriate to wish him a happy Jewish New Year, Woody Allen made it clear that such formalities were not necessary. “No, no, no,” he said with a chuckle, seated in an office suite at the Loews Regency hotel. “That’s for your people,” he told this reporter. “I don’t follow it. I wish I could get with it. It would be a big help on those dark nights.”

At 74, Mr. Allen, the prolific filmmaker and emblematic New Yorker, has hardly found religion. But the idea of faith informs his latest movie, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, which Sony Pictures Classics is to release next Wednesday. In the film, as the marriage of a London couple (Anthony Hopkins and Gemma Jones) unravels, the wife seeks comfort in the supernatural, which has unforeseen consequences on the marriage of her daughter (Naomi Watts) and her husband (Josh Brolin).

“To me,” Mr. Allen said, “there’s no real difference between a fortune teller or a fortune cookie and any of the organized religions. They’re all equally valid or invalid, really. And equally helpful.”

Mr. Allen spoke with Dave Itzkoff about his new film, how its themes resonate in his life and whether he has made his last movie in New York. These are excerpts from that conversation.

More

Monday, September 13, 2010

‘His Glory and His Curse’

by Charles Baxter

New York Review of Books

September 30, 2010

In his essay “Mr. Difficult,” Jonathan Franzen reports with a certain glum satisfaction that following the publication in 2001 of his third novel, The Corrections, he began to receive large quantities of angry mail. Some of the anger was sociological. “Who is it you are writing for? It surely could not be the average person who just enjoys a good read.” And some of it was just plain personal. One reader accused Franzen of being “a pompous snob, and a real ass-hole.”

Franzen’s novel spent twenty-nine weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and won the 2001 National Book Award. But no general readerly consensus seemed to exist concerning the book’s merits. The novel had hit a nerve, and it polarized its readers into two camps: those who hated it with particular venom, and those who felt it was a fine and beautiful book. (I was among the latter.) The author’s own ambivalence about the mass media didn’t help matters. After saying some indiscreet words about the Oprah Winfrey imprimatur on his novel’s book jacket, Franzen was disinvited from appearing on her show. It was a scandal, for a week or two.

The disagreements haven’t gone away. In his recent Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, David Shields denounces The Corrections without having read it: “I couldn’t read that book if my life depended on it,” he asserts. For him, Franzen’s novel—sight unseen—exemplifies “the big, blockbuster novel by middle-of-the-road writers, the run-of-the-mill four-hundred-page page-turner.” Shields claims that he is amazed that people still want to read such fiction. Oddly, what Shields seems to distrust about Franzen’s work (its mass appeal, its middleness) is exactly what the author’s enraged readers claimed The Corrections lacked. Was it still possible for a mass-audience novel to be artistically refined and thematically important? On this point there was no agreement because there hasn’t been any for decades.

More

New York Review of Books

September 30, 2010

In his essay “Mr. Difficult,” Jonathan Franzen reports with a certain glum satisfaction that following the publication in 2001 of his third novel, The Corrections, he began to receive large quantities of angry mail. Some of the anger was sociological. “Who is it you are writing for? It surely could not be the average person who just enjoys a good read.” And some of it was just plain personal. One reader accused Franzen of being “a pompous snob, and a real ass-hole.”

Franzen’s novel spent twenty-nine weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and won the 2001 National Book Award. But no general readerly consensus seemed to exist concerning the book’s merits. The novel had hit a nerve, and it polarized its readers into two camps: those who hated it with particular venom, and those who felt it was a fine and beautiful book. (I was among the latter.) The author’s own ambivalence about the mass media didn’t help matters. After saying some indiscreet words about the Oprah Winfrey imprimatur on his novel’s book jacket, Franzen was disinvited from appearing on her show. It was a scandal, for a week or two.

The disagreements haven’t gone away. In his recent Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, David Shields denounces The Corrections without having read it: “I couldn’t read that book if my life depended on it,” he asserts. For him, Franzen’s novel—sight unseen—exemplifies “the big, blockbuster novel by middle-of-the-road writers, the run-of-the-mill four-hundred-page page-turner.” Shields claims that he is amazed that people still want to read such fiction. Oddly, what Shields seems to distrust about Franzen’s work (its mass appeal, its middleness) is exactly what the author’s enraged readers claimed The Corrections lacked. Was it still possible for a mass-audience novel to be artistically refined and thematically important? On this point there was no agreement because there hasn’t been any for decades.

More

Sunday, September 12, 2010

French New Wave film director Claude Chabrol dies

AFP/Yahoo News

September 12, 2010

Prolific French film maker Claude Chabrol, who helped start the New Wave movement in the 1950s and went on to create some of the darkest portrayals on the silver screen, died on Sunday aged 80.

Chabrol was "an immense French film director, free, impertinent, political and verbose," Paris deputy mayor Christophe Girard, the city's top culture official, told AFP.

Born in Paris on June 24, 1930, Chabrol became famous for his sombre portrayals of French provincial bourgeois life.

Along with Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, he was an icon of French New Wave cinema, with all three writing for the renowned Cahiers du Cinema.

He authored dozens of films over more than 50 years, from his first work, Le Beau Serge, made in 1958 thanks to his wife's inheritance, to his last film, Bellamy, starring Gerard Depardieu which was released in 2009.

More

September 12, 2010

Prolific French film maker Claude Chabrol, who helped start the New Wave movement in the 1950s and went on to create some of the darkest portrayals on the silver screen, died on Sunday aged 80.

Chabrol was "an immense French film director, free, impertinent, political and verbose," Paris deputy mayor Christophe Girard, the city's top culture official, told AFP.

Born in Paris on June 24, 1930, Chabrol became famous for his sombre portrayals of French provincial bourgeois life.

Along with Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, he was an icon of French New Wave cinema, with all three writing for the renowned Cahiers du Cinema.

He authored dozens of films over more than 50 years, from his first work, Le Beau Serge, made in 1958 thanks to his wife's inheritance, to his last film, Bellamy, starring Gerard Depardieu which was released in 2009.

More

Friday, September 10, 2010

The Art of Ancient Greek Theater

The Scout Report

September 10, 2010

The Getty Museum provides this glimpse of Greek theater by utilizing both images and audio. Text at the website informs us that "Colorful characters, elaborate costumes, stage sets, music, and above all masks" were characteristic of Greek drama. Examples of images available to view on the site include sculpture and relief depicting actors. Many of these images feature actors wearing masks, such as Statue of an Actor as Papposilenos, dating from A.D. 100-199. In Greek myth, Papposilenos is the father of the band of satyrs that raised Dionysos. There are also over a dozen vessels to view; these vessels were used for various purposes including cooling wine, storage jars, and mixing vessels. The vessels are painted with scenes from the theater, and several are accompanied by audio of curators explaining the iconography. One of the featured items in the collection is a papyrus fragment from 175-200 A.D. with a few lines from a play by Sophocles. The exhibition closes with a reading, in ancient Greek, of an excerpt from this play, entitled The Trackers; a scene in which satyrs also appear, hearing music played on the then-newly invented lyre.

More

September 10, 2010

The Getty Museum provides this glimpse of Greek theater by utilizing both images and audio. Text at the website informs us that "Colorful characters, elaborate costumes, stage sets, music, and above all masks" were characteristic of Greek drama. Examples of images available to view on the site include sculpture and relief depicting actors. Many of these images feature actors wearing masks, such as Statue of an Actor as Papposilenos, dating from A.D. 100-199. In Greek myth, Papposilenos is the father of the band of satyrs that raised Dionysos. There are also over a dozen vessels to view; these vessels were used for various purposes including cooling wine, storage jars, and mixing vessels. The vessels are painted with scenes from the theater, and several are accompanied by audio of curators explaining the iconography. One of the featured items in the collection is a papyrus fragment from 175-200 A.D. with a few lines from a play by Sophocles. The exhibition closes with a reading, in ancient Greek, of an excerpt from this play, entitled The Trackers; a scene in which satyrs also appear, hearing music played on the then-newly invented lyre.

More

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)