New York Review of Books

December 10, 2015

Twenty-one Greek museums and four North American museums have cooperated to collect over five hundred artifacts from Ancient Greece in an extraordinary exhibition called “The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great.” The show went first to Canada (Montreal, then Ottawa), where it had 280,000 visitors. It is now on view at the Field Museum in Chicago, in a series of superbly lit rooms, and will continue to Washington, D.C., in May. The Greek museums were able to make good choices of a variety of important items to lend to the exhibition, including many works that had never been outside Greece. Richard Lariviere, the president of the Field Museum, told me he was glad to see the Greeks coordinate their effort without a need for him to negotiate with twenty-one different institutions.

After a few fertility-goddess figurines from the Cyclades, the show begins with a bang from Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations of sixteenth-century BC Mycenae, and it ends with a bang in the fourth-century tomb of Alexander’s father Philip II of Macedon at Vergina. The finds revealed a spectacular prosperity in both periods—not only in the profusion of gold artifacts but in the training of large numbers of craftsmen executing intricate designs. An elaborately sculptural vessel for sacrificial libations from Mycenae is as full of interactive curves as a Frank Gehry building, but it is carved from one solid block of alabaster.

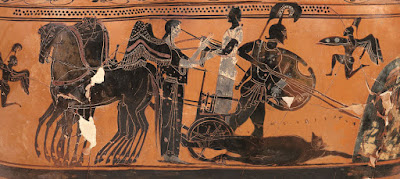

From the twelve centuries between the Mycenae and the Vergina findings, we are treated to well-selected vases, jewels, and statues. There are two kouroi from Boeotia—life-size nude statues of stylized young men, imitated from Egypt and teaching Greek sculptors how to carve large figures. There is also a kore—life-size young woman stylishly dressed. The vases include a black-figure lekythos that shows Achilles dragging the body of Hektor around the walls of Troy, and a red-figure kylix from Athens that shows Herakles defeating Antaeus by holding him away from his restorative earth.

More